There’s a certain pathos to watching an industry invent increasingly elaborate ways to convince itself it’s still needed. Enter “Human in the Loop,” or HITL as the acronym-obsessed tech world has christened it. This latest buzzword represents what may be Silicon Valley’s most audacious act of self-preservation: convincing us that artificial intelligence systems require human oversight not because they’re inadequate, but because we’ve graciously decided to remain involved.

The pitch is seductive in its apparent reasonableness. AI handles the heavy lifting, humans provide the wisdom and judgment. It’s a partnership, they tell us, a collaboration between silicon and flesh. But scratch beneath this veneer of cooperation and you’ll find something far less flattering: a desperate bid to maintain relevance in a world that’s rapidly automating us out of existence.

Goalpost

We’ve played this game before. When IBM’s Deep Blue conquered Garry Kasparov in 1997, chess ceased to be the ultimate test of human intelligence overnight. Suddenly, we discovered that real intelligence wasn’t about calculating moves but about creativity, intuition, emotional understanding. When AlphaGo demolished the world’s best Go players, we shifted the goalposts again. It wasn’t about strategic thinking anymore; it was about common sense, about understanding context, about the ineffable human touch.

Consider the irony: in most HITL systems, the human component is demonstrably the weakest link

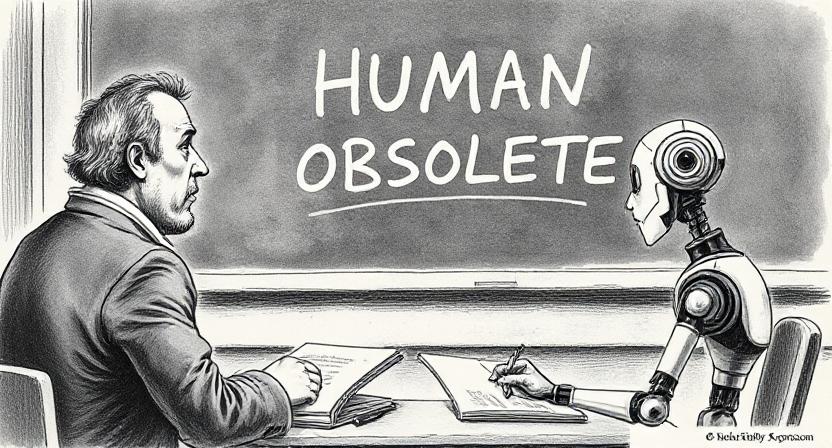

Now, as large language models draft emails, write code, and compose poetry with disturbing competence, we’ve retreated to an even more nebulous high ground: judgment. Oversight. The ability to know when something is “right” or “wrong.” This is where HITL comes in, offering us the consolation prize of remaining the final arbiters in our own obsolescence.

But here’s the uncomfortable question nobody wants to ask: If these AI systems are so capable that they can handle the complex work, why exactly do they need us to check their homework? And if they’re so unreliable that they require constant human supervision, what does that say about our rush to deploy them everywhere?

Follow the money

The answer, as usual, follows the money. HITL isn’t really about optimal system design; it’s about market psychology. Try selling a fully automated system to a nervous corporate buyer and watch their legal team have a collective aneurysm. But tell them there’s a human “in the loop,” someone who can be held accountable when things go sideways, and suddenly the purchase order materializes.

This is regulatory theater at its finest. We’ve created elaborate workflows where humans dutifully rubber-stamp AI decisions, not because their input genuinely improves outcomes, but because it makes everyone feel better about surrendering control to machines. The human becomes a psychological comfort blanket, a liability shield, a way to maintain the illusion that someone is still driving the car.

Explore Mobbin, a living library of mobile and web design patterns trusted by design teams at Uber, Meta, Airbnb, and Pinterest

Consider the irony: in most HITL systems, the human component is demonstrably the weakest link. Humans get tired, distracted, biased. We process information slowly and make errors at predictable rates. We’re the bottleneck in an otherwise efficient system. Yet we’ve convinced ourselves that our presence is not just valuable but essential.

We’re training our replacements

Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of HITL is how it resembles a training program designed to eliminate the trainers. Every human decision, every correction, every oversight action becomes data that makes the AI system more capable. We’re essentially teaching our replacements how to do our jobs better.

This process has an inexorable logic. As AI systems become more reliable through human feedback, the need for that feedback diminishes. The loop grows larger, the human interventions less frequent, until one day someone asks the obvious question: why are we still paying people to occasionally click “approve” on decisions they barely understand?

The manufacturing industry offers a preview of this trajectory. Factory floors once bustling with human workers gradually emptied as automation improved. The transition wasn’t sudden; there were years of “human-machine collaboration” where workers operated alongside robots, troubleshooting problems and handling exceptions. Sound familiar?

Judgment

Proponents of HITL often retreat to the castle keep of human judgment when pressed about our long-term relevance. Machines can process data, they argue, but only humans can truly understand context, weigh ethical considerations, and make nuanced decisions about complex situations.

This argument might be more convincing if human judgment weren’t so consistently flawed and biased. Study after study reveals the systematic errors in human decision-making: our susceptibility to cognitive biases, our tendency toward groupthink, our remarkable ability to rationalize self-serving choices. Meanwhile, AI systems make mistakes, but they make them consistently and measurably. They can be debugged, updated, improved.

Moreover, what we call “human judgment” often turns out to be pattern recognition operating on a dataset we can’t articulate. A doctor’s “intuition” about a patient, a judge’s sense of appropriate sentencing, a hiring manager’s gut feeling about a candidate: these seemingly ineffable human capabilities increasingly look like sophisticated but unconscious statistical analysis. And if that’s what they are, why wouldn’t we eventually build better statistical analyzers?

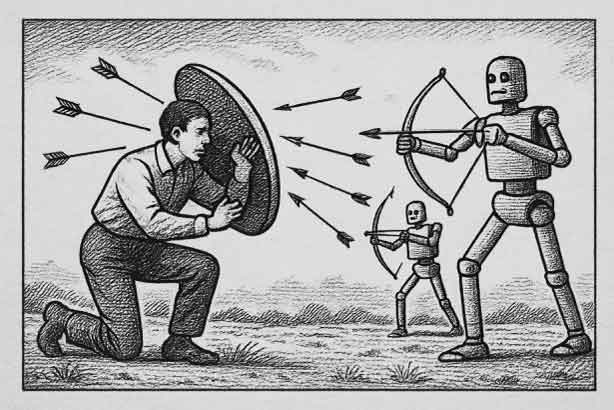

We’re not collaborators, we’re human shields

The language around HITL reveals its own contradictions. We speak of “collaboration” between humans and AI, but collaboration implies roughly equal partners working toward a common goal. What we actually have resembles something closer to a human apprentice shadowing a master craftsman, occasionally offering suggestions that are politely acknowledged before being ignored.

The AI doesn’t need us to think alongside it; it needs us to provide the legal and social cover for its decisions. We’re not collaborators; we’re human shields, absorbing liability and deflecting criticism when algorithms make choices that society isn’t ready to accept as purely machine-generated.

This dynamic becomes particularly clear in high-stakes domains like criminal justice or medical diagnosis. The AI system might correctly identify patterns that humans miss, but someone needs to take responsibility for the outcome. Enter the human expert, whose job isn’t really to improve the decision but to own it.

Precedent

This isn’t the first time humans have invented elaborate justifications for maintaining involvement in processes that no longer require us. The financial industry went through a similar transition with algorithmic trading. For years, human traders insisted that markets required human intuition, emotional intelligence, and the ability to read between the lines of economic data.

Today, algorithmic trading dominates financial markets, executing millions of transactions per second with no human intervention beyond setting initial parameters. The humans didn’t disappear overnight; they gradually became supervisors, then operators, then finally just the people who turn the systems on and off.

Where this goes

Which brings us to the uncomfortable truth that HITL advocates prefer not to discuss: if AI systems are on a trajectory toward greater capability and reliability, then human involvement becomes increasingly vestigial. We’re not building toward a future of human-AI collaboration; we’re building toward a future where human oversight becomes an expensive anachronism.

The question isn’t whether AI will eventually operate without human supervision; it’s how long we’ll continue to pretend that supervision is necessary. How many iterations of “but humans provide the wisdom and judgment” will we endure before acknowledging that the emperor’s new oversight responsibilities are more imaginary than real?

The question isn’t whether AI will eventually operate without human supervision; it’s how long we’ll continue to pretend that supervision is necessary

Perhaps the most honest assessment of HITL is that it represents a transitional technology, a way station on the road to full automation. It serves an important psychological function, easing our collective anxiety about surrendering control to machines. But like all transitional technologies, it carries within it the seeds of its own obsolescence.

The real test of HITL won’t be whether it makes AI systems better in the short term, but whether it prepares us for a world where human input becomes optional rather than essential. On that score, the jury is still out, though the verdict seems increasingly predictable.

In the meantime, we’ll continue to refine our loop-closing techniques, finding ever more sophisticated ways to remain relevant in systems that grow less dependent on us each day. It’s a noble effort, perhaps even a necessary one. But let’s not fool ourselves about where this particular loop is heading.